Moving Forward - Learning from the Past

Posted: Wed, 11 May 2022 13:44

Moving forward—learning lessons from history.

The 1960's were a period of great change and transition in all walks of life throughout the world. Vatican II still challenges the Church, sadly, with some doing all within their power to negate the strength and power of this ecumenical council. There was global awakening of the power of equality: sexism was seen to be wrong, while institutional racism needed to be confronted and stopped. In the USA, the great civil rights' leader, Dr Martin Luther King Jnr. was leading African Americans in a march towards equality. In a nation that had fought, and won, a bitter civil war to promote the equality of all citizens, the vestiges of racial discrimination were still too obvious, even in this decade of change. Dr King led peaceful, non-violent marches of freedom, especially across the southern states where the discrimination against the black population was horrendous and un-Christian. In spite of the violence of the white population, especially law enforcement agencies, Dr King and his supporters literally took the teaching of Jesus to heart, 'if you are slapped on one cheek, offer them the other!'

As a result of the Civil Rights' March through Birmingham, Alabama, Dr King was arrested. In early April 1963, he led a series of sit ins and marches to highlight the fact that African American citizens did not have equal rights—they could not live in white neighbourhoods, or have relationships with white friends. Schools, shops, restaurants, and, sadly, Churches practiced segregation. Black citizens did not have the vote and were often subject to summary justice by lynch mobs. Whatever way you look at the situation, certainly from a Christian perspective, Dr King was fighting for true justice. The local authorities in Birmingham, for all their deep biblical rhetoric, banned any meetings, boycotts and marches. Thus, many leaders of the Civil Rights' Movement saw themselves arrested and placed into Birmingham Jail for breaking local bylaws.

Thankfully, Dr King received support from some white churches, with Roman Catholic religious sisters being especially supportive. Even in the spirit of the emerging teachings of Vatican II, the Catholic Church leadership in the US did not cover itself in glory during these times. Support was not obvious, with a desire to keep the unjust status quo. Thankfully, as always, the Church did produce its prophets to speak out against this systemic evil. The great mystic and Trappist monk, Thomas Merton was deeply involved in the work of racial justice even from the peace of his rural retreat in Kentucky. He saw that this would demand making major sacrifices, including loss of 'white privilege' in terms of status and economic advantage. Merton believed that goodwill and charity were insufficient. He did not question liberal sincerity and generosity, but encouraged the creation and support of social, political and economic structures that were socially and economically just. He believed that social justice activism was an expression of God's love for the world. We are invited to offer a Church that must be inclusive, and all of us must live and mirror that inclusivity too. Merton's words written in the height of the US civil rights campaign in the 1960's can still speak to us today—I find that rather sad:

In simple terms, I would say that the message is this: white society has sinned in many ways. It has betrayed Christ by its injustices to races it considered "inferior" and to countries which it colonized. In particular, it has sinned against Christ in its lamentable injustices and cruelties to black people. The time has come when both White and people of colour have been granted, by God, a unique and momentous opportunity to repair this injustice and to re-establish the violated moral and social order in a new plane. ('Letters to a White Liberal' 'Blackfriars' 1963)

From his position of 'white entitlement', Merton offers a direct challenge to the local Birmingham religious leaders who wrote a common letter to Dr King while he was languishing in their local jail. They objected to his methods, urging that he follow the law—even a law that was unjust, urging Dr King and the African American population to be 'patient'. As the ancient Negro spiritual hymns prove, they had centuries of patience under their belt: they had fought in two world wars to eliminate injustice and the evils of discrimination. For white bishops and rabbis, including the Catholic Bishop of Mobile-Birmingham, to ask Dr King to be 'patient', seems that they did not really understand the urgency of the basic command to 'love the Lord, your God with you whole heart and soul, and your neighbour as yourself!'

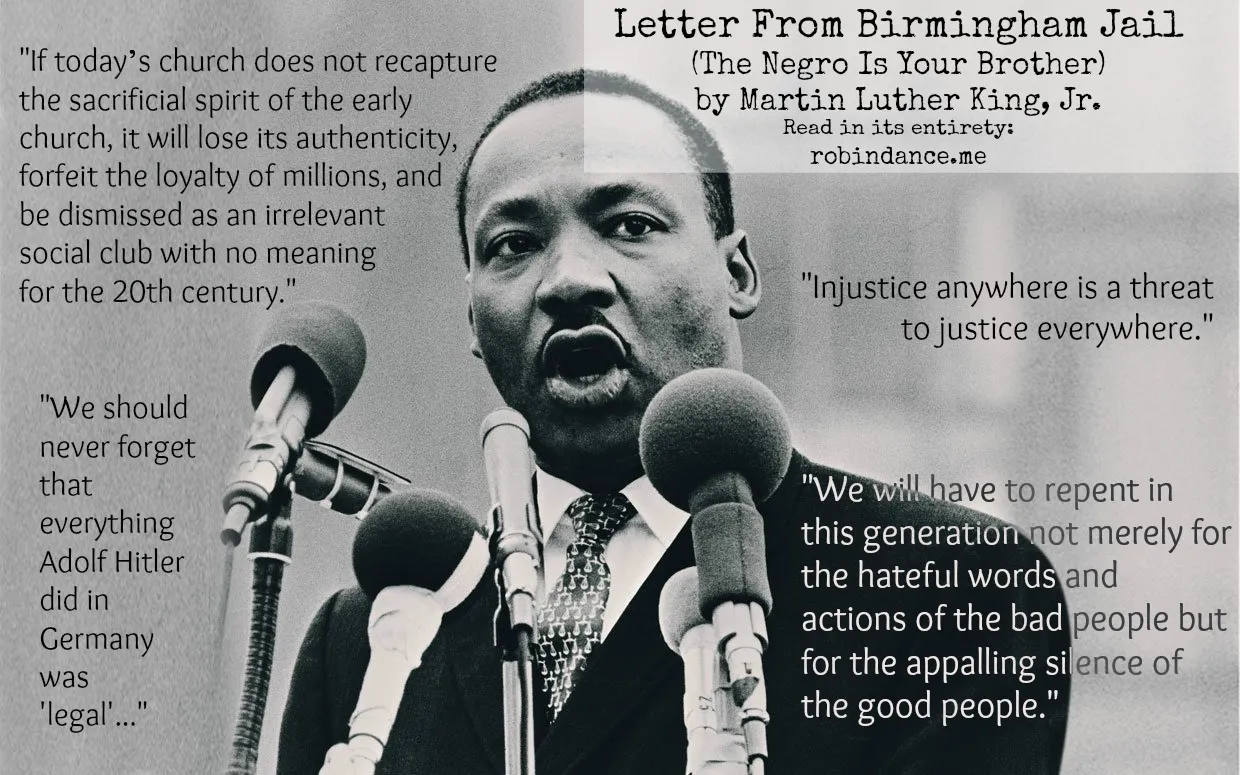

As one would expect, Dr King's response to these well-meaning white leaders was measured and challenging. His 'Letter from a Birmingham Jail' remains a spiritual classic that resonates in these divided times. A sign of the authority's fear of this prophet was they would not even give him writing paper to pen his reply—the letter was begun on the margins of newspapers smuggled into the jail. The white leaders urged King to fight his battles through the legal system and not on the streets. They saw Dr King as an agitator and an 'outsider' who was only in Birmingham to cause trouble. In his response to such accusations, Dr King countered that he was invited into a city that had suffered decades of injustice. Narrow minded parochialism had no place in this national campaign—what happened in Birmingham reflected on the whole nation, as he wrote:

Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere. We are caught in an inescapable network of mutuality, tied in a single garment of destiny. Whatever affects one directly, affects all indirectly ... Anyone who lives inside the United States can never be considered an outsider anywhere within its bounds.

His response to those men, who should have known better, reveals one who is committed to the Gospel. To be truly prophetic involves an acceptance of the tension that following the teaching will bring. It was a healthy tension that King hoped would bring white leadership to the negotiating table. He reflects:

We know through painful experience that freedom is never voluntarily given by the oppressor; it must be demanded by the oppressed.

When one is not subjected to the evils and violence of segregation, it is easy to make the call for patience and to avoid any tension. Racism is a sin that cries for justice and action that cannot be delayed. By not speaking out, there is a danger that we become complicit in the evil. Of course, some white Christians strove at great lengths and personal risk to abolish slavery, and many shed their blood in the war that emancipated slaves in the Southern states. Rightly interpreted, the Bible at the centre of the church has been an enormous force not only for the redemption of sinners but for the advancement of justice and charity. However, the exceptions were far too few. A multitude of Christian communities were silent in the face of slavery or even complicit in it. Dr King was fighting for the equality demanded by the US Constitution and the Civil War. Although the sin of slavery had officially been abolished, anyone with open eyes could see that the lot of African Americans, especially in the Deep South, had not really changed. What was especially horrific was that white Christians encouraged this division—the letter to Dr King from these religious leaders, perhaps, should not shock us. Perhaps they were still living in a Church that considered black people as unequal. As the author, Bryan Stevenson reflects:

The great evil of American slavery wasn't the involuntary servitude; it was the fiction that black people aren't as good as white people, and aren't the equals of white people, and are less evolved, less human, less capable, less worthy, less deserving than white people.

Dr King's Birmingham letter reminds his fellow church-leaders of the teaching of St Augustine that 'an unjust law is no law at all.' As followers of Jesus, all of us are called to uphold the just law of the land. The conditions endured by black Americans were a cry to heaven for the Church to act. Segregation was an evil that had to be addressed sooner rather than later. King took to heart the accusation that he was an 'extremist' because that was the position of Jesus. Jesus asked us to practice extreme love—even the love and acceptance of an enemy, as King wrote in his letter:

So the question is not whether we will be extremists, but what kind of extremists we will be. Will we be extremists for hate or for love?

He saw that these Birmingham religious leaders were not men of ill will, rather he felt that they were ill informed. Their lukewarm support of civil rights allowed the evils against the African American community to fester and grow. His call for non-violence stands against the reality of the Birmingham police department's violence against the supporters of civil rights. The letter certainly made the Catholic auxiliary Bishop of Mobile-Birmingham, Dr Joseph Durick to have a change of heart. The logic and power of King's argument made him a staunch supporter of civil rights. Ahead of his time in his ecumenical outreach, Dr King forced him to rethink his own inbuilt racism. He was unusual, among many of his contemporaries, in his whole-hearted support for the civil rights movement. With the teachings of Vatican II still wet on the page, Durick saw that he could not simply 'wait' for the sin of racism to end. He was branded a heretic by many fellow Catholics for his stand, with many organising walkouts during his homilies. It is interesting that these Christians used the very tactics that they accused Dr King of following! When Dr King was assassinated by a white supremacist, the Bishop held a memorial service and took part in the Memphis Civil Rights' March in 1968. His stand against the Death Penalty, prison reform and the Vietnam War are further examples that he took to heart King's call to be a 'Christian extremist.'

Perhaps it is time for white Christians to confess that we have not taken the sin of racism with the gravity and seriousness it deserves. The deep grief and anger over the death of George Floyd is about more than just police brutality. It speaks of a society and culture that allowed for the abuse and oppression of black Americans. The sin of segregation cannot be tolerated in any just society: Dr King's eloquent letter remains a constant reminder, especially to women and men of God, that we cannot sit on the side-lines. 'The Good Samaritan' stepped in when the priest and Levi refused to help—he was even prepared to the foreigner. Pope Francis reminds us of the demands of being fully pro-life:

My friends, we cannot tolerate or turn a blind eye to racism and exclusion in any form and yet claim to defend the sacredness of every human life.

We are called, as children of God, to live out God's mission by ensuring that we protect and defend our brothers and sisters that are suffering. We must stand up against inequality and fight for every person, and we must do so with the peace and faithfulness that Jesus exemplified in His own life.

Author: Fr Gerry O'Shaughnessy SDB

Image: Robin Dance